Legislation looks to ban PFAS in tampons, cosmetics and more

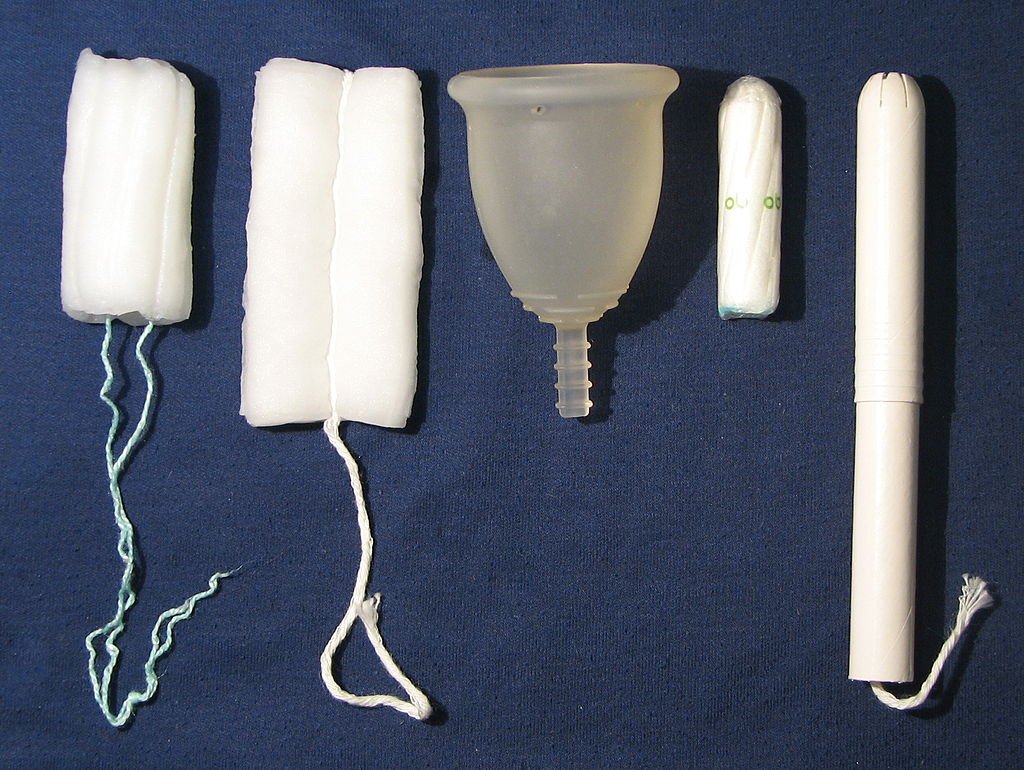

Menstrual products, via Wikimedia Commons.

A new Senate bill would prohibit the manufacture and sale of cosmetic and menstrual products and textiles containing PFAS and dozens of other materials dangerous for people and the environment.

The Senate Committee on Health and Welfare read the bill, S.25, for the first time Jan. 20, but it likely won’t be addressed until the committee votes on bills related to reproductive health care, child care and, possibly, regulating tobacco and vape products.

Lead sponsor Sen. Ginny Lyons, D-Chittenden, who chairs the committee, said the bill’s progress has been slowed down because the committee has had to prioritize other public health issues made more pressing by the Covid-19 pandemic.

But committee members are concerned about high levels of PFAS — or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — in groundwater, especially in southern Vermont and ski towns such as Killington, Stowe and Fayston. S.25 would be a continuation of efforts in the Legislature to regulate the toxic chemicals. S.20, passed last session, banned PFAS from firefighting foam and equipment, children’s products and ski wax.

Despite the regulations last session, ski clothing made with PFAS was grandfathered in and is still permitted in Vermont, something the new bill would nix. Manufacturers use PFAS to make ski clothing waterproof. But Lyons said that when the textile gets wet, the chemicals can get caught in water droplets and drip onto snow, causing surface- and groundwater contamination.

The bill would also ban the use of PFAS in making menstrual products like tampons, pads and period underwear — some of which have been found to contain PFAS. These products pose increased health risks for people with periods because they are used in close proximity to skin tissue that can more readily absorb chemicals.

Lyons anticipates pushback from manufacturers in Vermont during the public comment period for S.25. Representatives from the Associated Industries of Vermont, a group representing manufacturers that monitors legislation, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Neither did members of the Vermont Chamber of Commerce’s lobbying team.

But written testimony on the bill last session from the chamber might reveal the perspective of Vermont industries on the issue.

Chamber vice president Chris Carrigan raised concerns in the March 2021 testimony about supply chain issues and economic disadvantages the bill could cause for manufacturers during the pandemic.

Carrigan said then that the definitions of PFAS and other chemicals in the bill were too broad and advocated for further scientific testing and evidence before regulating any other forms of PFAS.

The new bill also addresses other chemicals in personal care products that pose health concerns.

The human carcinogen benzene can be found in many drugstore products such as hand sanitizer, spray sunblock, spray dry shampoo and conditioner and spray deodorant.

Chemicals called phthalates — used to improve the longevity of nail polish, lotions, hair products and more — have also been proven to cause cancer and other health problems in humans and animals.

And hair straighteners and other straightening products, often marketed toward women and especially women of color, contain the carcinogen formaldehyde.

Lyons sees the use of these chemicals in personal care products as “paradoxical” and “ridiculous” given the possibly “deadly” results from exposure over time.

“We see products put into women’s cosmetics preferentially to make women look beautiful and at the same time kill us,” Lyons said.

Marguerite Adelman, a Winooski activist involved in water and pollutant issues, had measured praise for the bill.

“S.25 is a great bill,” Adelman said. “It moves us forward from her original bill that didn’t cover as much as this bill will cover.”

But Adelman said she wishes the bill went further and regulated PFAS in personal protective equipment and clothing worn by members of the Vermont Air National Guard stationed in the Burlington area.

Adelman is a member of the Vermont PFAS/Military Poisons Coalition, a project of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which started in response to the Department of Defense stationing F-35s at the Burlington airport..

She said the military has been “one of the biggest contaminators” and that she cares about the health of military personnel, their families and citizens nearby.

Both Lyons and Adelman have qualms with the current strategy of the federal government when regulating PFAS.

“We don’t adhere to any principles of prevention or precaution in this country, which we should,” said Lyons, who thinks the government should ban the entire class of chemicals rather than take a case-by-case approach.

Only 29 out of about 10,000 PFAS chemicals can be tested currently, but PFOS and PFOA are the only two forms of PFAS regulated on the federal level. The current federal regulation strategy allows companies to change chemical formulas slightly and still put products with PFAS on the market, Adelman said.

This leaves PFAS regulation up to the states; Vermont would be leading the charge on PFAS regulation with S.25 as most states either just uphold Environmental Protection Agency standards or have none at all.

The list of chemicals that would be restricted in the bill can cause cancers and chronic illness in humans and have a negative impact on the health of plants and animals. Given this, Lyons believes S.25 is fundamentally an “environmental justice and social justice bill.”